Modding an old game which hardcodes nearly everything (LEGO Island 2) part 1 of 2

Source code: https://github.com/RobbeBryssinck/LegoIsland2Reversing.git

TL;DR: if you are a beginner in reverse engineering games, part 1 might be interesting to you. If you want to hear my ideas on how I modified a game which is not very extensible due to a lot of things being hardcoded, part 2 might be more interesting to you.

I recently dug up an old pc game from my childhood, LEGO Island 2, which is an action adventure game with several maps and a semi-open world. There is this one NPC, a train conductor, who can fly around the map and picks you up when you step onto the train tracks. I always wanted to be able to freely fly around the map like him, preferably at the press of a button, without having to go to a flying vehicle first. In this blog post, I will attempt to mod the game to do just that.

I decided to make this a 2-parter, since I came across some unexpected difficulties while attempting to mod the game, namely the fact that the game is not very extensible in the way that it handles entities and movement. I figured it was interesting to discuss the subject in a separate post. In part 1, I will reverse engineer the major parts of the game, namely the player object, the entity list, and the game loop, and in part 2, I will discuss several strategies on how to implement a fly hack with the restrictions at hand, and finally implement the fly hack itself.

Reverse engineering the game

Before analyzing the game, I will lay out the tools that I will be using.

- Ghidra: Ghidra is a disassembler and a decompiler that will be used to analyze the game code itself.

- x32dbg: x32dbg is a modern debugger that can debug 32-bit PE executables.

- ReClass: ReClass is a tool used to reconstruct structs and classes.

- Cheat Engine: Cheat Engine is a memory scanner, which I will use to find objects in memory and to find static pointers.

- Notepad: for writing notes.

Plan of action

The binary itself is 6257 KB large. It is unreasonable to simply open the binary in Ghidra and start analyzing the entire code. Instead, I will have to build a frame of reference first. I will start by reversing the player struct, since I have the most control over the player object. Changes in values will help me find the initial object itself. From there, I can analyze what functions access this object. Since players and NPCs often share a lot of code in game design, one of these functions is bound to lead me to the entity list, which is the second major target. Once I have the entity list loaded into ReClass, I can manipulate each entity individually. The third and final target is the game loop. The game loop sits at the root of the program, iterating over each entity and updating them according to the game state. This is the ultimate target, since this gives me an ultimate understanding of the overall architecture of the game.

The player struct

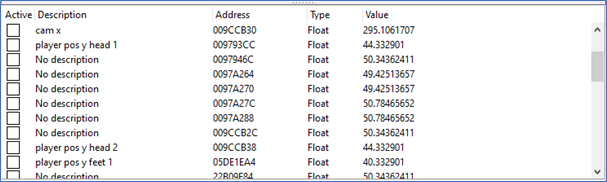

A good method of finding the player struct is by scanning the memory for property values. In this scenario, I used the player position coordinates. Player coordinates are often saved as floating points. Using Cheat Engine, I scanned the memory for an unknown floating-point value. Next, I walked up a hill, so that I can be sure that the Y value has increased. Then, I scanned for increased values. This gave me hundreds of thousands of results. I walked down the hill in-game and scanned for decreased values. This still gave me too many values to work with. I simply repeated this process a bunch of times, until I got it down to about 50 possible addresses. I figured out that a certain value belonged to the camera position since only that value changed when rotating the camera, meaning that that cannot be the player position. I also noticed that there were two values that were exactly 4 off from each other. By walking up a hill, I estimated that the lower value is the player’s feet, and the higher value is the player’s head.

The problem with the current list is that the values are all contained in static pointers. This is something that games often do: saving certain values like position both in the dynamically allocated object of the player and in a global variable. To keep those in sync, the dynamically allocated will periodically update the global variable. I scan the memory space again, only this time, I scan for the exact float value of the player’s y coordinate. This returned two addresses: the static address and the dynamic address.

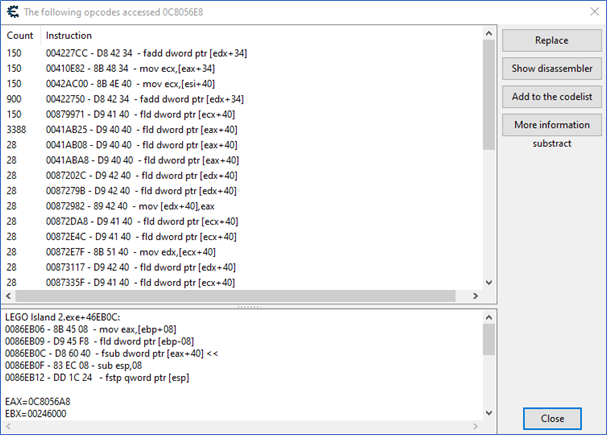

With this, we now have an address somewhere in the dynamic player object. We do not know where in the struct the player coordinates are. To find that out, Cheat Engine can be used to see what accesses the coordinate. Presumably, the coordinate is accessed by loading the player object address into a register and accessing the offset of the coordinate.

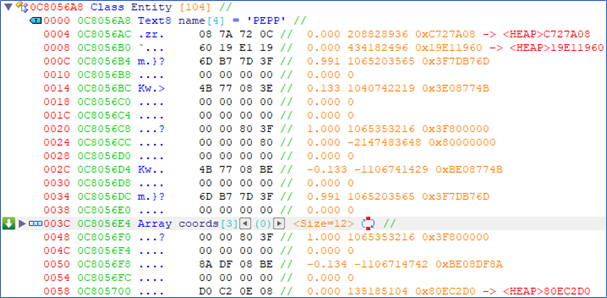

Most of these instructions access the coordinate by an offset of 0x40. I arbitrarily choose to analyze the third instruction. Presumably, esi would contain the base address of the player object. The address of esi is 0x0C8056A8. I pasted the address into a new class in ReClass. ReClass shows every piece of data in as many forms as possible: ASCII, float, hex, decimal. When looking at the first 4 bytes of the struct, it spelled out PEPP. The name of the main character is Pepper. At this point, I am reasonably confident that this is the player object.

The entity list

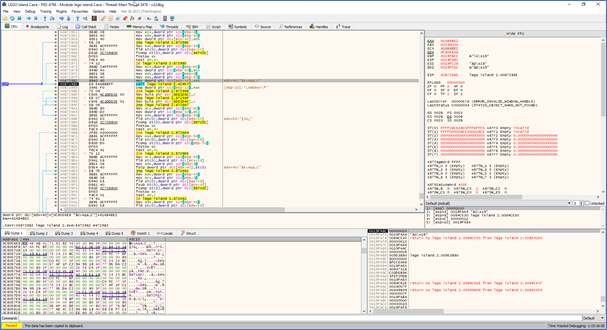

Next up on the list of objectives is the entity list. Now that we have the player object, we can start figuring out where the entity list is located. One strategy would be to attach x32dbg, put a breakpoint on the y coordinate of the player object, and see how the object was loaded in memory in the surrounded code, preferably through Ghidra for the actual code analysis. If the object pointer is passed as a parameter to the function that accesses the coordinate, then x32dbg can be used to look at the saved return pointer on the stack to see which function passed the argument and called the function. This function can in turn again be analyzed in Ghidra.

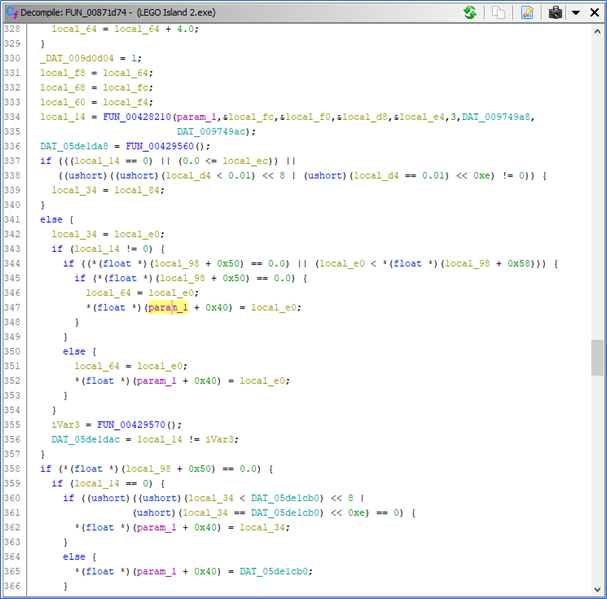

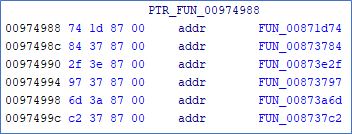

As expected, the decompiled code shows that the player object is passed to the current function as a parameter. When cross referencing the function, there is only one instance of this function being referenced, which is in the data section, next to other function pointers. It seems to be some sort of self-crafted virtual function table.

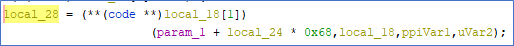

To find the code that called the function, I look at the stack in x32dbg. The saved return pointer points to a function that called the previous function through a register. This makes sense, since there is no cross reference to any direct function calls. When looking at the function call in the decompiler in Ghidra, the first argument, which previously was the player object, is passed. The interesting thing is that the argument is passed dynamically. The argument is calculated by using the first parameter of the current function as a base and calculating the offset by multiplying some integer by 0x68.

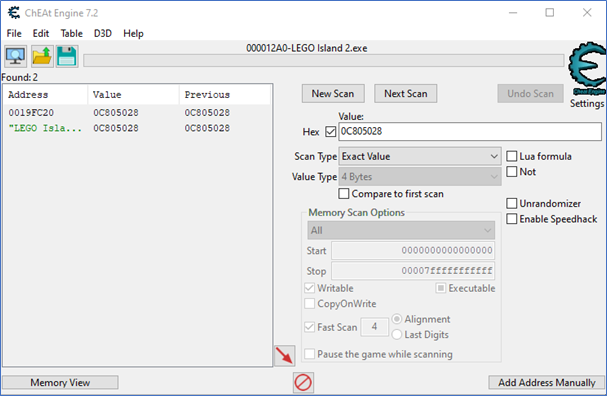

When looking at the surrounding code, the function call is nested within a loop. Each iteration, the variable “local_24” is increased by 1. By all indications, this code loops through the entity list and passes it to a dynamic function. Using x32dbg’s stack view, we can look at 4 bytes after the saved return pointer, which is the first parameter aka the start of the entity list. The address is 0x0C805028. Cheat engine can be used to scan the memory for this address, which might return a static pointer that stores the entity list.

The scan returned two results. When looking at the first result, the address is in the stack range. This is the entity list pointer stored on the stack. The second pointer is a static pointer. It is safe to assume that this is the entity list pointer.

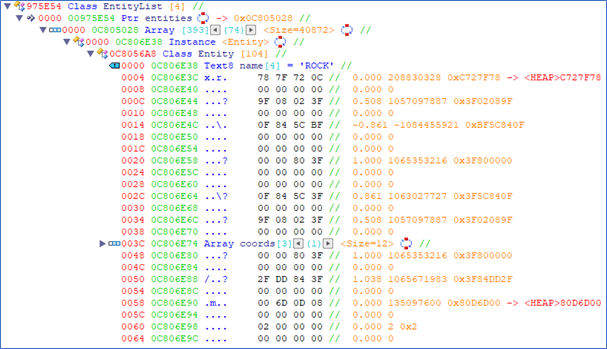

One more interesting find from the entity loop code is that the iterator is multiplied by 0x68 bytes, indicating that each entity is 0x68 bytes large. In ReClass, we can increase the size of the Entity class to 0x68 bytes. We can also make a new class of 4 bytes that simply points to the entity list. We can set the destination type to be a list of entities. By doing this, we can scroll through all the entities. This will also survive when restarting the application, since the base pointer is static.

The game loop

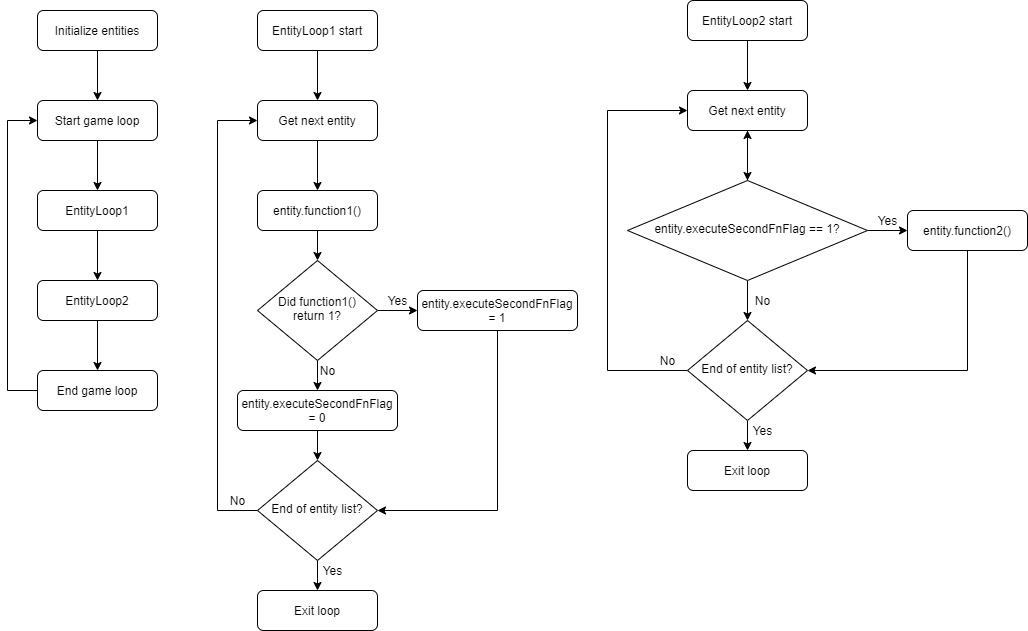

When finding the entity list, we came across a function that loops over every entity and executes a function from a virtual function table, presumably linked to that type of entity. We can use this as an entry point to find the overarching game loop. I renamed the entity loop function to “EntityLoop1”.

At this point, I still have x32dbg attached and paused from the entity list. The next step is to find out what called the entity loop function. Like before, I looked at the stack in x32dbg and followed the saved return pointer in Ghidra.

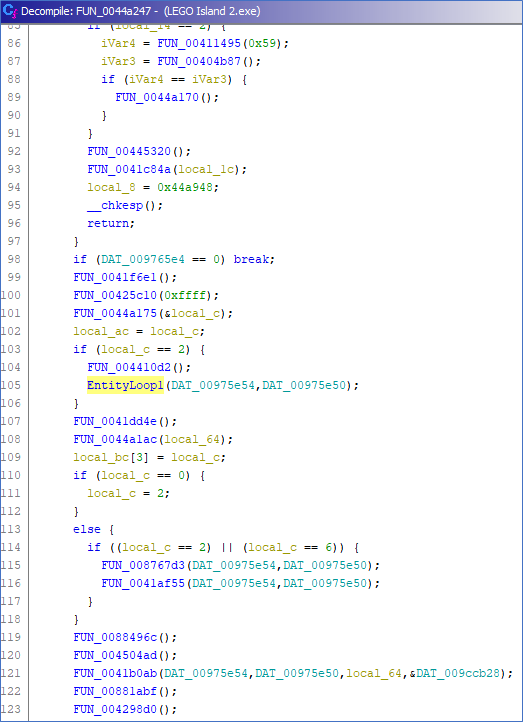

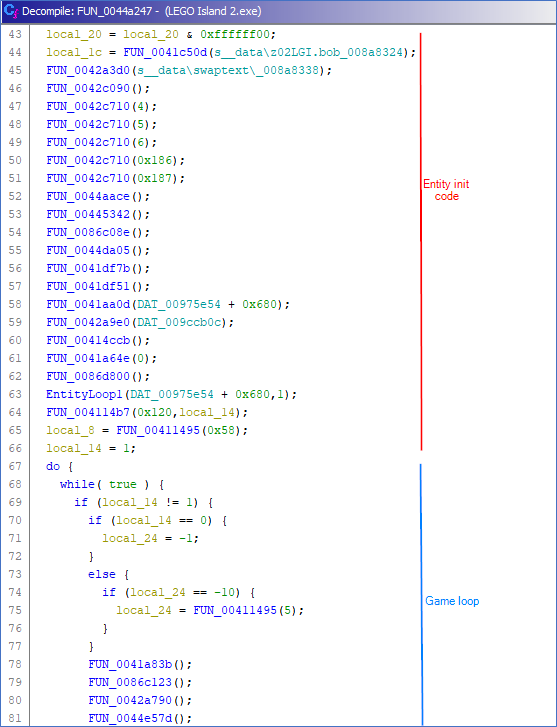

The function call passes two global variables. The first one, as expected, is a static pointer to the start of the entity list. EntityLoop1 is called within a “do.. while” loop. The while condition is “true”, meaning that the loop runs forever. It is safe to assume that this is the game loop, but to be sure, I traced the call stack back to its origin. When going up two more times, we end up in WinMain, which is the first function that gets executed (outside of PE setup).

The interesting thing about the presumed game loop function is that it, again, is not a function that is called somewhere directly, but instead, is saved in the .data segment as a function pointer and called dynamically through a register. At this point, I did some testing by reloading the game a few times, and each time, it loads the same game loop function. The next thing I tried was going to a different zone (since the game is divided into different “zones” or “worlds”), and this time, the game loop function was not the same. From this, we can derive that each zone has its own custom game loop function. The entity list is also dependent on what zone it is in, since the initialization code of the entity list is done in the game loop function, right before the actual loop. One last tidbit gathered from the game loop function: the length of the entity list is passed to the EntityLoop1 function, so that the function knows how many iterations it needs to loop for.

There is one more function in the game loop that accepts the entity list and the entity list size as the first and second argument, respectively. We will call this function “EntityLoop2”. EntityLoop2 gets called after EntityLoop1. After some experimentation, I have found that EntityLoop1 and EntityLoop2 each iterate over different functions in the hand-crafted function tables of the entities. Take vehicle entities for example. In EntityLoop1, it will execute a vehicle’s function from its function table. This function will check whether the player is entering the vehicle. If so, it will return “1”, if not, it will return “0”. This result is used to change a variable in the vehicle’s entity object, indicating that the player has entered the vehicle. When EntityLoop2 iterates over that same vehicle next, and it sees that the player has entered the vehicle, it will execute the second function in the entity’s function table, which handles the movement of the vehicle itself. If this variable is not set because the result of the first function in EntityLoop1 is “0”, the function will not execute. I made some diagrams to visualize the process.

Conclusion

Now that we have a decent (albeit somewhat simplified) picture of what the architecture of the game looks like, we can start thinking about how to build a fly hack. Based on this post, the game might seem pretty modular: it has entity lists which are looped through to execute update functions and these “virtual” functions can (and sometimes are) reused. That said, several aspects of the game’s architecture makes the game less flexible than it should be, namely due to how it instantiates objects and hardcodes many things like the entity creation per map and the static assignment of possible entities. I will explain this in more detail in part 2, where I will also create the final hack.