Modding an old game which hardcodes nearly everything (LEGO Island 2) part 2 of 2

Source code: https://github.com/RobbeBryssinck/LegoIsland2Reversing.git

In part 1, I reverse engineered most of the relevant parts of the code. In this post, I will look at how to extend the functionality of the game to allow me to fly using a fly hack.

Strategy

To implement the fly hack, I decided to use the glider object. The glider is a vehicle that is unlocked at the end of the game. It can be used to freely fly around the map. Since the animations and movement most represent flying, I decided to go with this vehicle. As we know, the entity list is meant to be immutable: the size and types of entities are set in the initialization code of the map. In my initial strategy, I researched how the entity list is constructed, so that maybe I could add my custom glider to that list when initializing the map.

The glider object

To start, we have to find the glider object in memory. Since the entity list is always the same, the glider object should always be at the same position in the entity list. With this in mind, we can use a debugger to break when the memory at the address of the glider object gets written to during initialization of the entity list. It should write “GLDR” there, which is the shorthand name for the “glider” object. I copied the memory address of the instruction that wrote the “GLDR” string, and jumped to that address in Ghidra to analyze the surrounding code. This didn’t go quite as planned.

Ghidra was unable to decompile the entire function due to a time out. When looking at the size of the function, things became clearer. The function was a whopping 156,579 bytes large. Scrolling through the function, there were other shorthand names being written to the entity list. Presumably, this function initialized the entire entity list directly, without any function calls to object specific initializers or constructors. This would not be too bad if this gigantic function initialized everything linearly, so that initialization code specific to a certain object was at least right next to each other, but this is not the case. After letting execution continue and looking at the glider object in memory when the game finished loading, more initialization took place in some other function, given that the object looked different from when the massive initializer function was just done with the snippet of code that initialized the glider’s name and such.

void MassiveInitializator()

{

...

// Initialize NPC 1

...

// Initialize glider

...

// Initialize car 1

...

// Initialize glider some more

...

// Initialize NPC 1 some more

...

// Initialize glider some more

...

}If I want to recreate the glider initialization code and add a new one to the list over which I would have full control, I had to hunt down any possible code that initializes the glider object and recreate it. This is what makes the game so inextensible: the entity (list) initialization is hard coded, without any straightforward way to add a new object on demand.

A new strategy

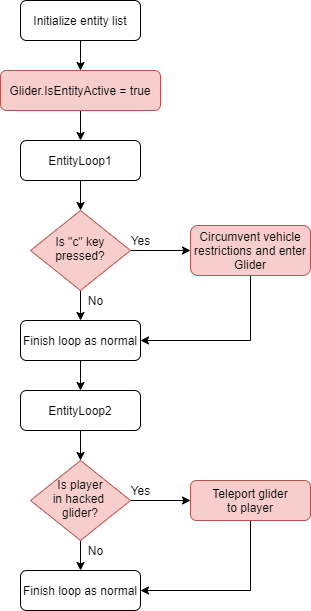

Since adding a new object to the entity list is looking less and less of an option, we have to find another way to fly. We can still use the glider object, but we could circumvent the restrictions so that it essentially acts as a fly hack. The goal is to have the glider always be available, and to have it teleport to the player at a custom key press. The function that checks whether the player can enter the vehicle is executed in EntityLoop1, and the function that controls the movement is executed in EntityLoop2. As explained in the first part of this series, EntityLoop1 and 2 are loops that are used to iterate over each entity and execute particular functions attached to the entity object.

This is what it looks like when the player enters the glider normally:

And this is what it looks like when using the finished fly hack:

The fly hack can be implemented in the following 4 steps:

- If the glider is not already unlocked at this point in the game, set the “IsEntityActive” flag to true in the Glider object. Remember that, even if the glider is not yet unlocked at a certain point in the game, the glider object will still be initialized and present in the entity list, it’ll just be set to “inactive”.

- Vehicles in the game have a distance restriction, namely that the player needs to be in a certain radius before they can enter. This check can simply not be present in the hooked code.

- To enter a vehicle normally, the player needs to have pressed the “control” key. We can instead check if they pressed another key to trigger the fly hack, like the “c” key, which allows the “control” key to be used for normal vehicles.

- Once the player has entered the vehicle, the glider needs to be teleported to the player, which can be done by fetching the player’s coordinates and setting the Glider object’s coordinates to that. This has to be done right before the movement control function in EntityLoop2 is executed, otherwise the player will be teleported to the glider instead.

The process is visualized in the flowchart below. The white squares represent the original code, and the red squares represent the injected code from the fly hack. I also included some pseudocode of the process.

void GameLoop()

{

InitializeEntities();

Glider.IsEntityActive = true;

while (true)

{

EntityLoop1();

EntityLoop2();

}

}

void EntityLoop1()

{

// Loop through entities and execute their first functions...

Glider.IsInEntryMode = Glider.CheckEnterVehicle(Glider); // will be hooked

// Continue looping through entities...

}

void EntityLoop2()

{

// Loop through entities and execute their second functions...

if (Glider.IsEntered)

Glider.ControlFlyMovement(); // will be hooked

// Continue looping through entities...

}Crafting the fly hack

We need to hook two functions: the function that handles entering a glider, and the function that handles the movement of the glider. I crafted both hooks in assembler, since the code was not too complicated. We will start with the entry hook.

Entry hook

The first three instructions are responsible for checking the KeyStroke variable to see if the ‘c’ key was pressed in this iteration of the world state loop. If so, the variable will hold the value 0x80. That is why the one-byte dl register is compared to 0x80. Next, the code checks whether the player is already in a vehicle. This is done by calling an in-game function which takes a value, in this case 0x5E, and uses that value as a key in a global dictionary. The function returns the value linked to that key. The return value is then ANDed with 1. If the player is in a vehicle, the return value will be an even number, so the AND operation will return zero and the function will end early.

Then, the entity will be checked to see if it is a glider or not. Coincidentally, there is another entity that uses the glider entry function to check whether the player wants to enter. That entity is the Pteranodon. We want to prevent the Pteranodon from being used in our custom code. Remember that the first 4 bytes of an entity are its shorthand name. That is why, in the custom assembly code, I compare the first value of the entity to 0x52444C47, which is the little-endian version of “GLDR”, aka the shorthand name of the glider.

Finally, if all these checks pass, the address of the glider entity is moved into the EnteredVehicle variable (which is a global variable that stores the currently entered vehicle), and execution jumps back to the original glider entry function. The only difference is that it returns to the part in the function where it returns 1. Below, I wrote some pseudocode of the injected code.

int CheckEnterVehicleHook(vehicle)

{

if (KeyStroke == 'c' && !Player.IsInVehicle && vehicle.name == "GLDR")

{

EnteredVehicle = vehicle; // vehicle is Glider

return 1;

}

else

{

return 0;

}

}Fly movement hook

The fly movement function needs to be hooked to teleport the glider to the player’s location. This is not the only function of the hook, however. The first time that the fly movement function is called after entry, the function will also perform some initialization code. To perform this, it will check whether the “control” key was pressed. In our hack, we use the “c” key, so this check will fail and the game will consequently crash. To fix this, we need to execute the initialization code within the fly movement function after entering the glider through the hack. To do this, I simulated the checks in the hook, only this time, I again checked whether the “c” key was pressed instead of the “control” key.

The first instructions in the hook check whether the glider is still in “entry” mode. The glider entity has a variable for this at offset 0x23, which should have the value 3 if it is still in entry mode. Next, I check whether the ‘c’ key is pressed. The last part of the check is checking whether the passed entity to the movement update function is the glider, and not the Pteranodon, by comparing the entity passed to the fly movement function to the saved entity in the global EnteredVehicle variable.

The last part of the hooked code is teleporting the glider to the player. This is done in 4 instructions per coordinate. First, the player object is loaded into edx. Next, the coordinate is loaded into the ecx register. Following that, the glider entity is loaded into edx. Lastly, the saved player coordinate in ecx is saved in the coordinate of the glider entity. This is done three times in total; once for each coordinate. Lastly, execution will jump back to the original fly code. Again, I included some pseudocode of the injected code below.

void FlyMovementHook(glider)

{

if (glider.IsInEntryMode && KeyStroke == 'c' && EnteredVehicle == glider)

{

glider.x = Player.x;

glider.y = Player.y;

glider.z = Player.z;

UpdateMovement(glider);

}

}Conclusion

At this point, the fly hack works: the player can fly at any point at the press of a button. The hack can be further improved by modifying the speed, removing restrictions like flying angles, or, to be fancy, remove the model of the glider so that it looks like the player is flying on its own.

With this mini blog series, I mainly tried to show how to make use of existing objects in memory when simply spawning a new entity to do your bidding is either not feasible, or overly complicated.